2025 Summer Student Program Rethinks California’s Wildland-Urban Interface

Today, nearly one-third of Americans live in the “wildland-urban interface,” or WUI—a turbulent zone where suburbs meet wilderness, infrastructure meets ecology, and a warming, drying climate raises the stakes for how we live and build. In California, where cities continue to expand into fire-prone terrain due to a statewide housing crisis, the WUI is particularly fraught and consequential.

This tension is at the heart of SWA’s 2025 Summer Student Program, which brought together seven graduate students in SWA’s Laguna Beach studio for an immersive month-long exploration of Southern California’s WUI. Working with local experts—including a wildfire ecologist, former fire marshal, and biogeographer—students visited active sites across Santa Barbara County and, for their final presentations, developed planning proposals for a 175-acre parcel.

Then, right as the program wrapped up, Governor Gavin Newsom signed two landmark reform bills affecting the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)—a move poised to accelerate infill housing, exempt certain wildfire mitigation projects, and shift how California balances development with environmental review. Though the decision’s reaction is complex and still unfolding, the timing underscored the relevance of the students’ work: reimagining the wildland-urban interface not just as a risk zone, but a testing ground for policies and practices that could shape the future of growth across the state.

From the outset, the program emphasized the WUI as more than a boundary, but a design challenge threaded through statewide issues of housing affordability, public health, ecological stewardship, and equitable development. Taken together, the students’ projects offer a diverse set of strategies. Below are a few common threads that emerged.

1. Agricultural land can serve as both a fire buffer and a development framework.

Two proposals took up the challenge of Santa Barbara County’s eroding agricultural belt—once a de facto fire buffer, now under pressure from speculative development and water scarcity. Rather than accepting this loss, both students propose reconfiguring agriculture as an active interface between housing and fire-prone wildlands.

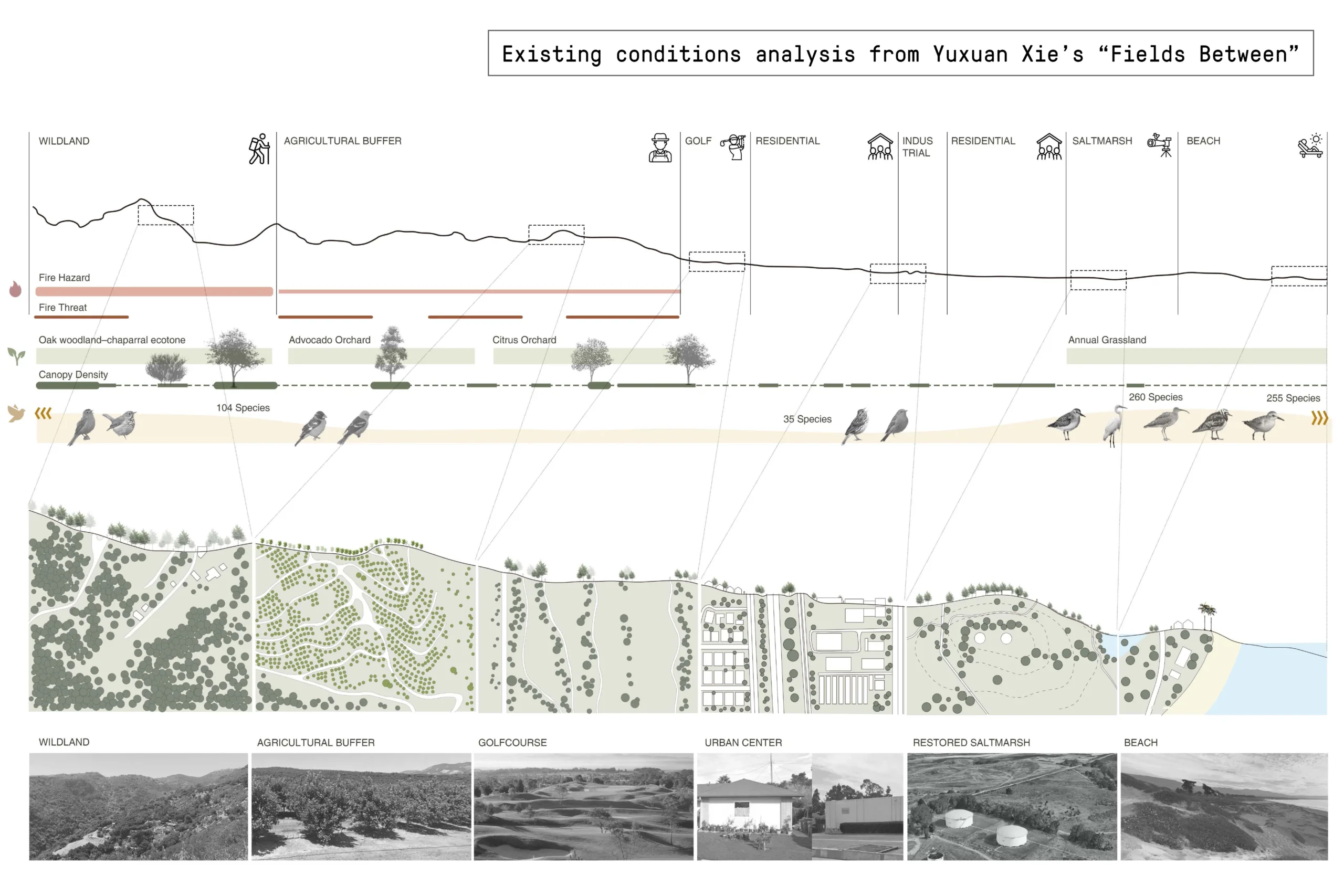

Yuxuan Xie’s “Fields Between” overlays the site with an agritourism corridor structured by oak belts, citrus rows, and riparian trails. These planted systems are calibrated to intercept downslope fire movement while supporting a seasonal program of harvesting, recreation, and low-density ecolodge housing. Adjacent orchards are leased to local farmers, while smaller plots are maintained by residents and school groups through stewardship agreements.

Phumisit “Jaab” Veskijkul’s “Blurring the Edge” takes a more community-scaled approach, proposing compact housing clusters embedded in a fire-adapted agricultural framework. Each cluster is flanked by defensible zones managed by tenant-farmers, nonprofits, or resident stewards, with graywater capture systems supporting small-scale citrus and native plant cultivation. The goal is not preservation per se, but reintegration—bringing agriculture, housing, and fire management into alignment.

2. Policies tackling California’s housing and wildfire crises must be addressed together.

Several students directly engaged with the site’s recent upzoning, testing policy frameworks that could simultaneously deliver new housing and reduce fire exposure.

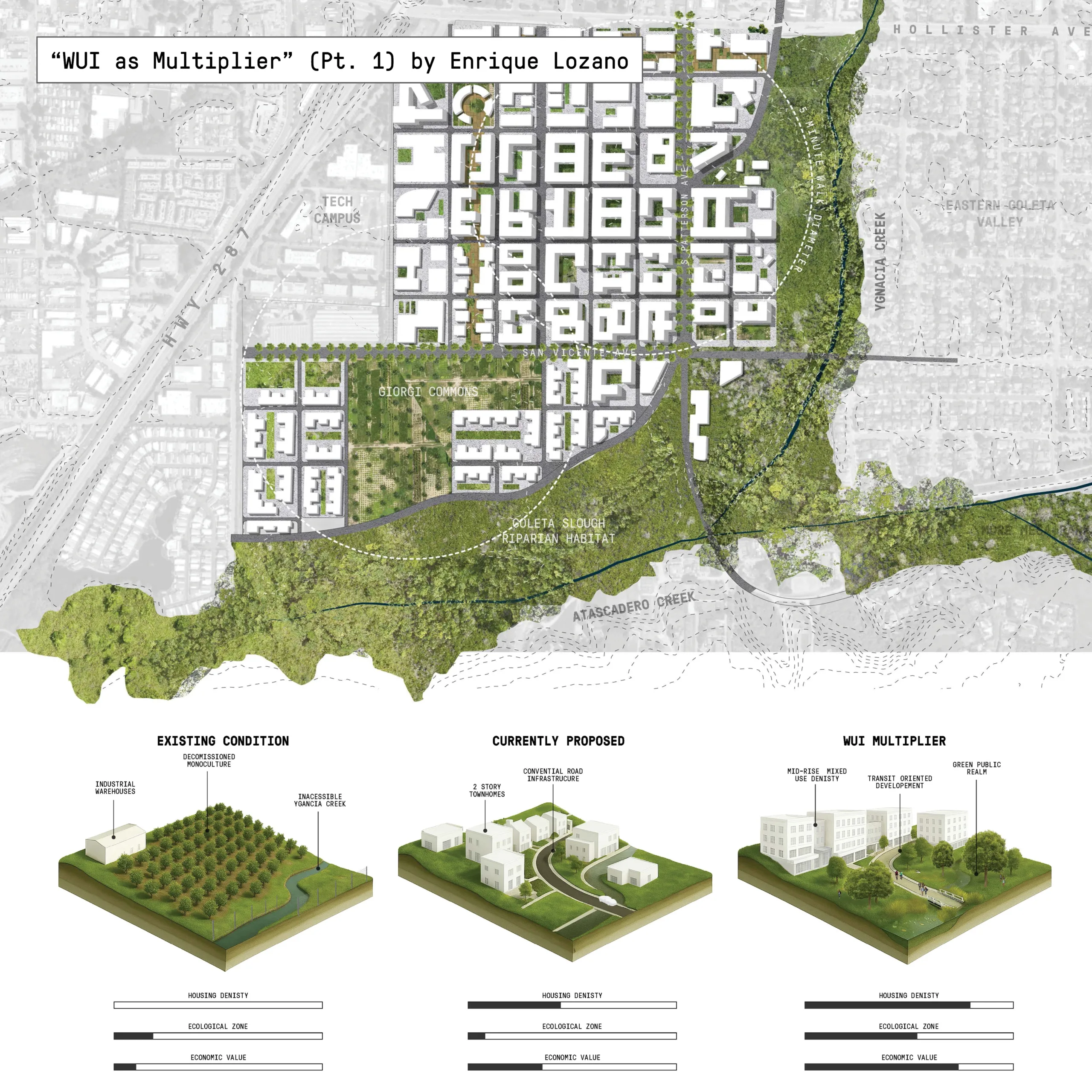

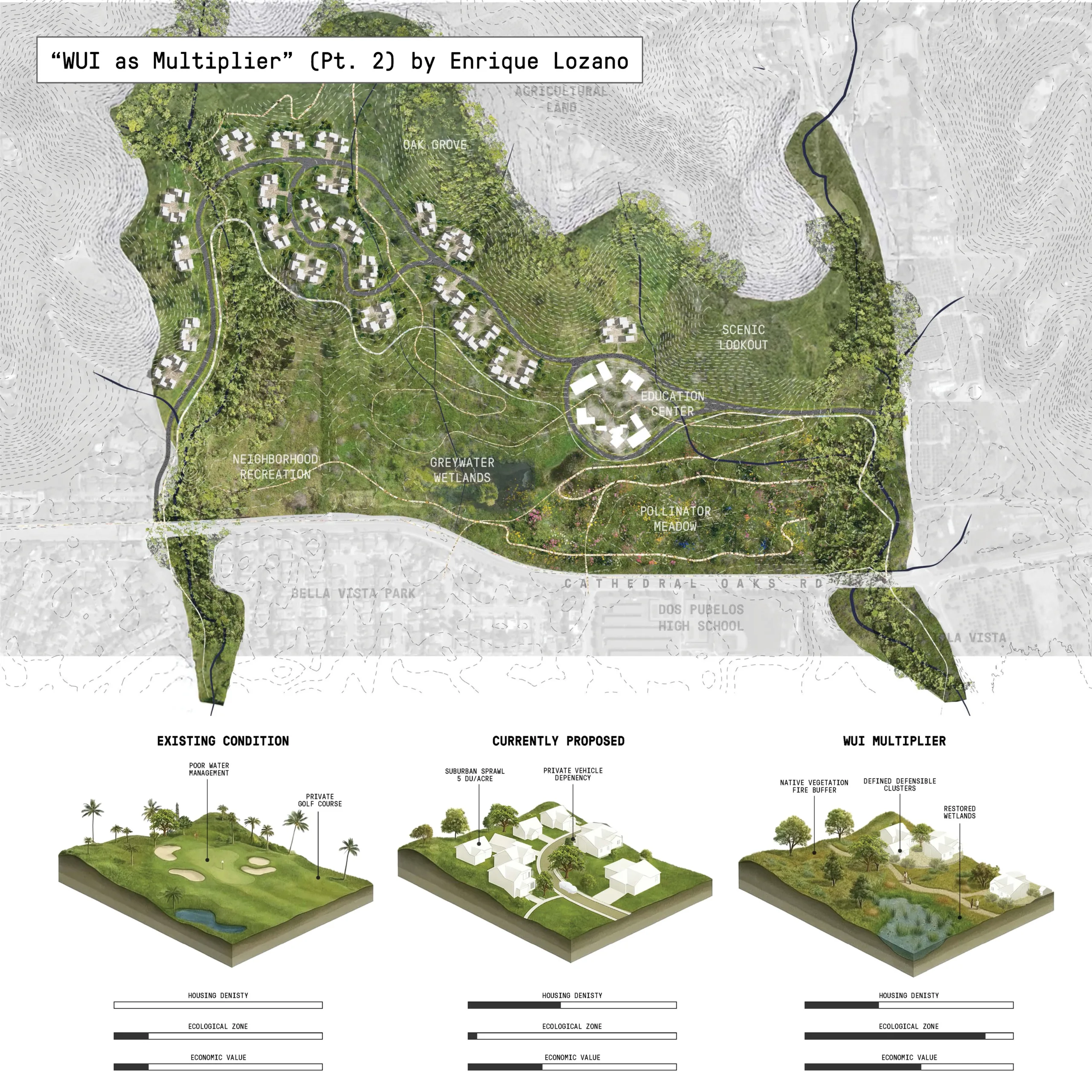

Enrique Lozano’s “WUI as Multiplier” proposes a Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) program linking the site to a nearby farm. Instead of building 1,000 units in a fire-prone WUI parcel, developers could transfer rights at a 1:1.5 ratio to urban receiving zones closer to transit and emergency services. The sending zone could then be restored as a fire buffer, while the receiving site accommodates higher-density housing tied to mobility upgrades, riparian restoration, and public space.

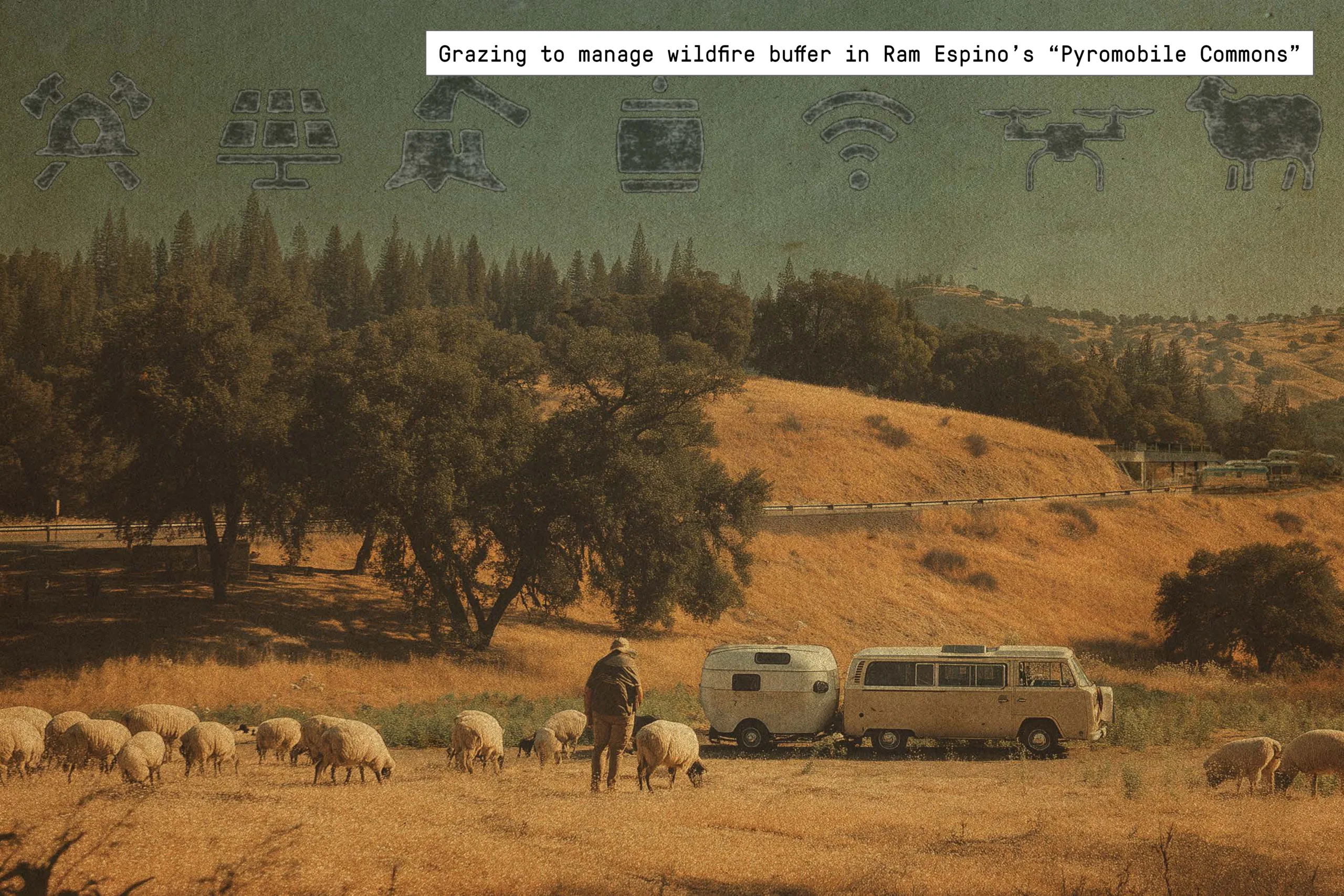

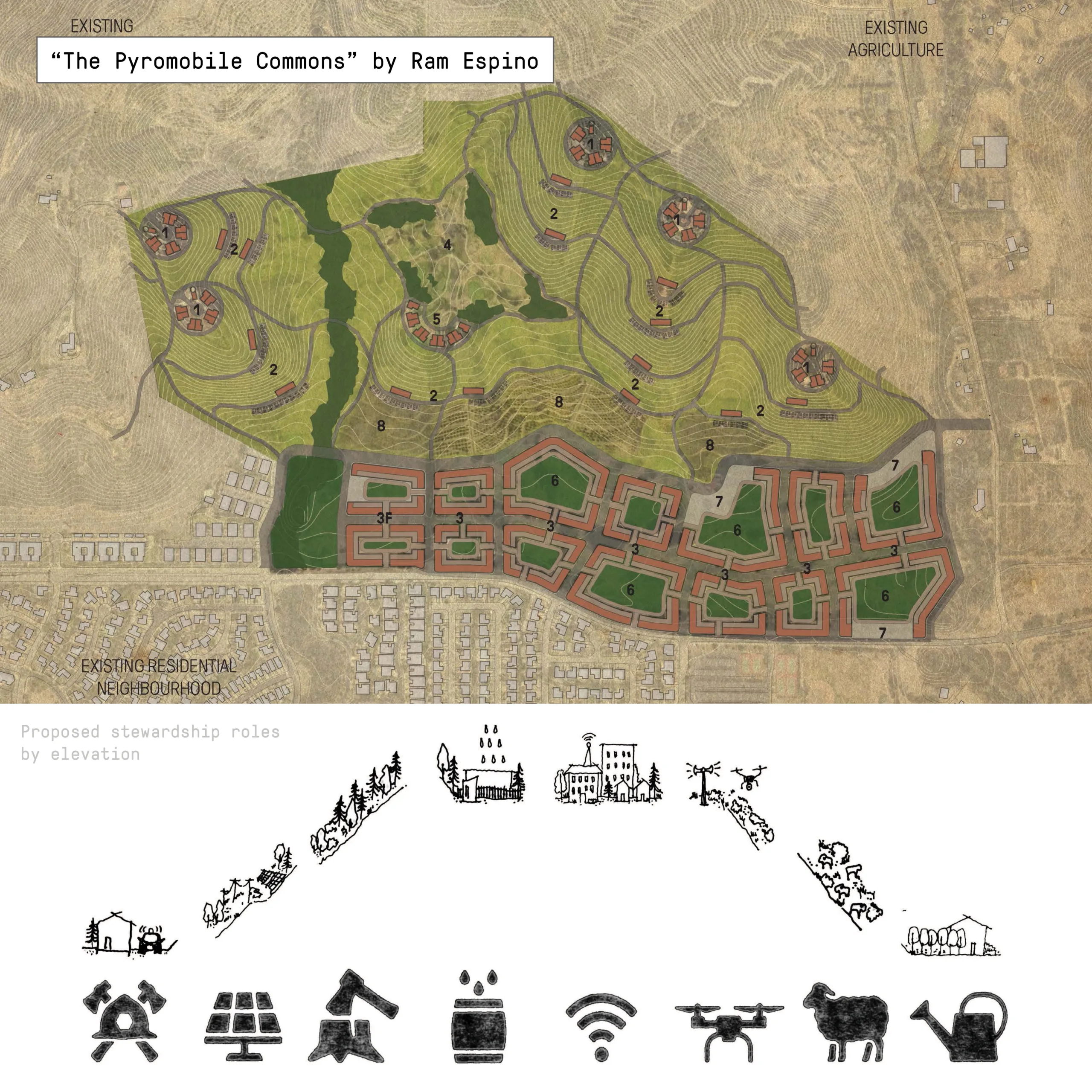

Ram Espino’s “The Pyromobile Commons” critiques fixed housing patterns by introducing a phased mobility-based system. Lower-risk areas support mixed-use residential blocks; mid-risk slopes are occupied by mobile homes tied to seasonal work or wildfire response functions. The model is less about blanket densification than negotiating where and how density can shift as fire risk and infrastructure capacity change.