“I believe that parks, trails, playgrounds and recreation centers are critical infrastructure in a modern city,” Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson said in his State of the City address in November 2022. “When I was growing up in Dallas, families like mine depended on our city parks.”

In the address, Johnson urged city leaders to focus on the “Three P’s” — public safety, potholes and parks — in a billion-dollar bond package that will go before voters next year.

A bond committee with an appointee from each city council district will develop and negotiate the final spending plans, but a parks-specific task force will focus on the parks section of the bond.

Recently, the Dallas Park and Recreation Board created a list of all the parks needs that could be included in the package.

The list totals $662 million.

JR Huerta sits on the park and recreation board for District 1 and will be the district’s representative for the task force.

He estimates roughly $333 million, half of the needs list and a third of the total bond package, will be allocated to parks. Huerta’s job is to “fight to get more” and to make sure the needs of Oak Cliff are fairly met.

Johnson, who regularly references his childhood as an Oak Cliff and West Dallas native, made a similar promise in his address. When discussing elaborate plans for a trail system that will connect much of the city north of I-30, Johnson said he also plans to bring that “long-overdue infrastructure” to Oak Cliff.

“I promise you that we will not leave this part of the city where I grew up behind,” Johnson said.

The Boom

The billion-dollar bond package comes only 14 years after 2009, when a budget deficit caused the city to slash parks funding down to the bare bones.

Across the country, cities are experiencing a parks renaissance.

Many people credit the pandemic with encouraging people to take advantage of parks and return to the outdoors. But Huerta says people have “been at parks this whole time,” especially in Oak Cliff.

District 1 ranks second out of the city council districts for access to parks, Huerta says. After all, parks are in our neighborhood’s history. In the 1920s, George Kessler — the namesake for the Kessler Park neigborhood — worked on Fair Park beautification and developed a plan to contain the Dallas floodway. Around that same time, philanthropist Martin Weiss donated land to the city, hoping to see public facilities and parks bloom in his neighborhood.

“People feel like it’s always North Dallas that gets improvements, but we have such beautiful parks in Oak Cliff that it’s hard for us to keep saying that we don’t have access to them,” Huerta says.

And plans for even more parks and green spaces are booming.

Late last year, city council member Chad West proposed Westmoreland Park as the site for Dallas’s next skatepark. It could be the first update Westmoreland Park has received since 2012 and a major step in increasing skatepark infrastructure in Dallas.

Currently, Dallas has only one completed skatepark. Compare that to San Antonio’s 16, Houston’s eight and Fort Worth’s four, and it is clear we have fallen behind.

Since the skatepark plans were first introduced, parks department members and West have said they intend to target the 2024 bond for some of the funding needed.

Kevin W. Sloan Park, which will replace the Jefferson/12th Street connector, is set to begin construction this year. Plans for the park were started under council member Scott Griggs, who preceded West, and it is named after the landscape architect who designed the park before his death in 2021.

Huerta says plans for the Sloan Park are currently out to bid, and a construction company could be selected as soon as this summer.

Sloan Park, which has been in talks among neighbors for more than 10 years, is an example of how things “bubble up” in the parks department.

“I thought I knew everything about parks and how they operate, and I know a lot of it,” Huerta says. “But now that I’m on the inside, I can see that sometimes things bubble up. And I think the community doesn’t understand that things bubble up, there’s a lot of red tape to go through.”

The red tape is why Huerta sometimes recommends pursuing public-private partnerships on parks projects. As someone who has worked on both the private and city side of the parks department, he says he “knows how to help the public get things done” faster than the city is often able to.

For some reason, Huerta says, people can be put off by the idea of a public-private partnership.

But he points to Klyde Warren Park downtown, which is heralded as a crown jewel for the city and is now being replicated in other cities and in Oak Cliff across I-35, as an example of exactly how a public-private partnership can work.

Bridging I-35

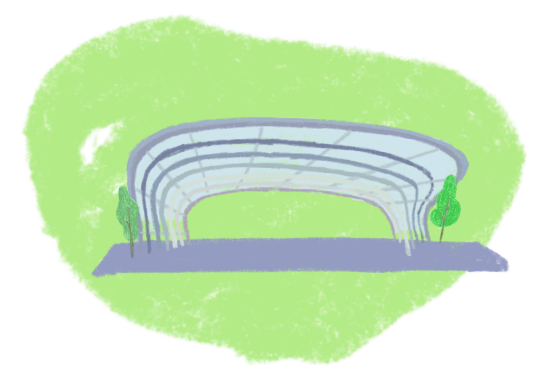

When the Texas Department of Transportation began thinking about reconstructing I-35E in 2017, community meetings were held to discuss the opportunity to build a deck park with the same basic infrastructure as Klyde Warren Park.

TxDOT and The Southern Gateway Foundation say the Southern Gateway Deck Park is an opportunity to “right the wrong” that happened 50 years ago, when I-35 was built through the historically Black neighborhoods in Oak Cliff.

“One woman said to me, ‘If we get this right, this will not be turf. This will be common ground to all the young people of our neighborhood,’” says Chuck McDaniel, managing principal at the landscaping architecture firm SWA that has helped design the new deck park. “They’ll come here, it’s bright and shiny and new, it’s as good as anything they have anywhere else in Dallas, and this will represent common ground.”

McDaniel and Ryan Blaylock, a principal at the HKS firm and SWA’s collaborator on the park’s design, say including elements of Oak Cliff culture into the park were essential to telling the “deeper story” of the park.

In the 1950s, a prominent street in the neighborhood that was ravaged by I-35E was 12th Street.

Once the park is finished, a 16-foot-wide pedestrian footpath called the “12th Street Promenade” will mark where the street once stood. It will be paved by stones engraved with the names of famous or pivotal Oak Cliff residents throughout history.

Vegetation local to Oak Cliff will be planted throughout the park, and in the children’s play areas, the ground will be decorated with the imagery of leaves of local trees.

The deck portion of the first phase of the park, which spans from Ewing Avenue to Lancaster Avenue, has already been completed, and construction is expected to begin this summer. According to the Southern Gateway Foundation, the park could be open to the public by the end of 2024.

“What this will do for the community in and around (the park) is probably the biggest thing,” Blaylock says. “It’s going to allow people areas where they can go and get access to Wi-Fi that they may not have access to at home. Other areas around the park and other developments will flourish.”

But for some neighbors, the idea of flourishing development spurred by the deck park is worrisome.

In a March press conference, residents of the 10th Street Historic District — the historically Black neighborhood that originated as a Freedman’s town and was hemorrhaged from Oak Cliff during the development of I-35E — voiced their concerns about the deck park.

“We keep hearing that they’re trying to stitch communities together, but what communities are they talking about?” asked resident Patricia Cox. “Money for the park is not money for Black history.”

Tenth Street residents have said they are worried development spurred by the deck park will be the final nail in their already struggling neighborhood’s coffin.

The Southern Gateway Foundation has held community meetings to field feedback from neighbors who may have questions or concerns about the park, but distrust still persists among some residents — especially those old enough to remember the days they could walk down to Zang Boulevard without braving the highway underpass.

A 10-minute walk

Over a quarter of Dallas residents are unable to walk to a park in less than 10 minutes.

It’s an improvement from 2014 numbers, which saw half of Dallas residents living further than 10 minutes from a park or greenspace. But still, the nonprofit Trust for Public Land would like to see that number shrink even further.

Trust for Public Land called on 300 mayors to pledge to increase walkable park or greenspace options for their residents in 2017, and Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings was the fifth mayor in the country to join the campaign.

Since then, Mayor Johnson has recommitted to the pledge.

“Dallas has had the good fortune of having two back-to-back mayors who really cared about parks,” says Robert Kent, the Texas State Director of TPL. “You pair that with coming out of COVID, when basically the whole world was like, ‘Where do you go? You go to the park.’ That year, year and a half, when we were really in the thick of it, every single day people were walking to the park.”

Huerta believes in the vision of the 10-minute walk pledge.

In District 1, he says two major hot zones persist near the Hampton and Clarendon neighborhood and Zang and Jefferson area. The parks department is in the process of buying land for a pocket park, but positioning the park in a way that children will not have to cross the busy Hampton Road is a priority, he says.

“The parks department is taking that into a factor. Even if a park is sitting just across the highway from you, can a child really cross the highway to get there?” Huerta says.

But while District 1 is a model for the 10-minute walk pledge in Dallas, the Southern parts of Oak Cliff need help. According to Trust for Public Land, 46% of residents in the Five Mile Creek Watershed still can not walk to a park.

Plans for 16.7 miles of trails and 125 acres of park land could help fix that.

Adopted by the city in 2019, plans for the Five Mile Creek Greenbelt are being spearheaded by Trust for Public Land. The original plans for the widespread trail system were devised in the ’50s.

Kent says the organization is “picking up on an 80-year promise.”

The trail is planned to connect with Chalk Hill Trail on the west side, and The LOOP trail on the east, to create a Dallas-wide network of trail systems.

Known as the 1954 Bartholomew Plan, the Dallas Parks director at the time, L.B. Houston, said the trail could be “comparable to certain sections of Turtle Creek Parkway,” which now connects 86 acres of parks and playgrounds.

TPL has purchased 125 acres of land for three parks across the planned greenbelt.

Kent calls the parks “emeralds on a string.”

The first park, Renaissance Park, was completed in 2021 after the principal of South Oak Cliff High School approached Kent about an empty plot of land adjacent to the school.

TPL partnered with the urban planning nonprofit Better Block to develop the space, which features Wi-Fi and an outdoor classroom, a basketball court, a rain garden, climbing walls and gym equipment.

And, on the north end, the park opens out onto the paved Cedar Crest Trail, which will link to the greenbelt, once completed.

The trail is planned to be completed in eight sections, and Renaissance Park connects to the third section. The first section of the trail will be 2.41 miles and connect Westmoreland Park to Kiest Park.

It is “shovel ready,” Kent says, once funding is sorted out and finalized.

The biggest challenge facing parks is funding, Kent says. TPL is looking into state and federal funding, as well as private fundraising and grants to fund the trail.

The Dallas bond package could also be a help.

Dallas currently spends $115 per resident on its parks a year, Kent says. He would be willing to pay “double that.” Kent points to Plano, where $225 a resident is spent on parks, as a city that is “doing it right” when it comes to prioritizing parks and green spaces.

“We are willing to spend $115 bucks on a lot of stuff that provides a lot less value. Parks are the steal of a century,” Kent says. “Imagine what would happen if we thought of our parks as being as important as our hospitals for public health.”