Houston is an expanse of kinetic chaos. Its patchwork mosaic resists legibility, organization, and hierarchy. It’s also beset by a number of existential crises, some natural but most manmade. In light of these qualities, is coordinated change possible? And can architecture create positive systemic shifts?

Houston Genetic City responds to these questions with a resounding yes. The book, published by Actar last year, is a speculative set of proposals that emerged from a year-long studio at the University of Houston Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design. All professors at the school, authors Peter Jay Zweig, Matthew Johnson, and Jason Logan present an assemblage of interventions that explore the complex nature of Houston’s social, environmental, and economic challenges. Varying geographies and questions are considered, mixed with a speculative collection of experimental, acupunctural, and ecologically minded urban interventions.

The Genetic City hypothesis presents Houston as a spatialized profit equation codified by unpredictability and rapid change. Instead of a capitalistic shortcoming, this unpredictability and rapid change are presented as opportunities—evidence of adaptation, mutation, and diversity. The Genetic City embodies these ecological qualities, but with new direction: from the status quo of “resource exploitation and geographic divisions” to a dynamic ecology of “resilience and interconnection.”

This effort updates late 20th century ideas about architecture and urban form. “The Generic City,” Rem Koolhaas’s essay from S,M,L,XL, is used as a framing device for the book, which changes a single letter to graduate from the generic to the genetic. Such a projection, and the transdisciplinary results that follow, reflect the involvement of Thom Mayne, who was a collaborator and guest critic throughout the process. His influence is also seen in the graphic language, the formal composition of structures, and the knotted intersection of infrastructural, ecological, and social functions that give rise to urban form.

The book prompts many questions concerning disciplinarity and the future of allied design professions. Is architecture “just” form generation? Is architecture the design of systems and ecologies? Where does architecture stop and urban design start? Lately it’s too simple to assume the viability of “Here’s a problem, here’s a diagram, here’s a building.” The book is related to the increasingly robust discourse of ecological urbanism, which suggests a broader efficacy through transdisciplinary urban practice that prizes systemic and ecological operations rather than icon creation, however green or responsive. Even Thom Mayne acknowledges that shapes don’t cut it anymore: “It often seems like everyone wants to make a new shape. But I’ve been doing this for thirty years and I think there are enough people doing that—making new shapes. Well, is it even an important problem, to come up with a new shape?”

Mutation is welcome, but it’s no match for the profit motive that remains at Houston’s core. In the imagined future, it’s clear that the architect is essential in addressing wicked problems, but it’s also implied that the architect remains beholden to private capital. While not addressed explicitly in the book, big questions arise: Can a discipline with an unaltered model of practice achieve this vision? Who might build these transformative interventions?

One answer is found in the book’s interview with Gerald D. Hines. Discussion of Hines’s Galleria and Pennzoil Place show how developers, and the architectural projects they facilitate, can spark innovation and initiate broader change. But not all developers are so enlightened; if they were, wouldn’t Houston be a museum showcasing the revelatory nature of developer-driven projects? This isn’t exactly the case. It’s important to consider the quality and directionality of these transformations, but to use the tools at hand to realize different outcomes.

Through ambitious student work, Houston Genetic City provides examples of what alternative urbanisms might look like and how they might evolve. The projects, each led by one of the professors/authors, take three different approaches: Developer City, Energy City, and Unzoned City.

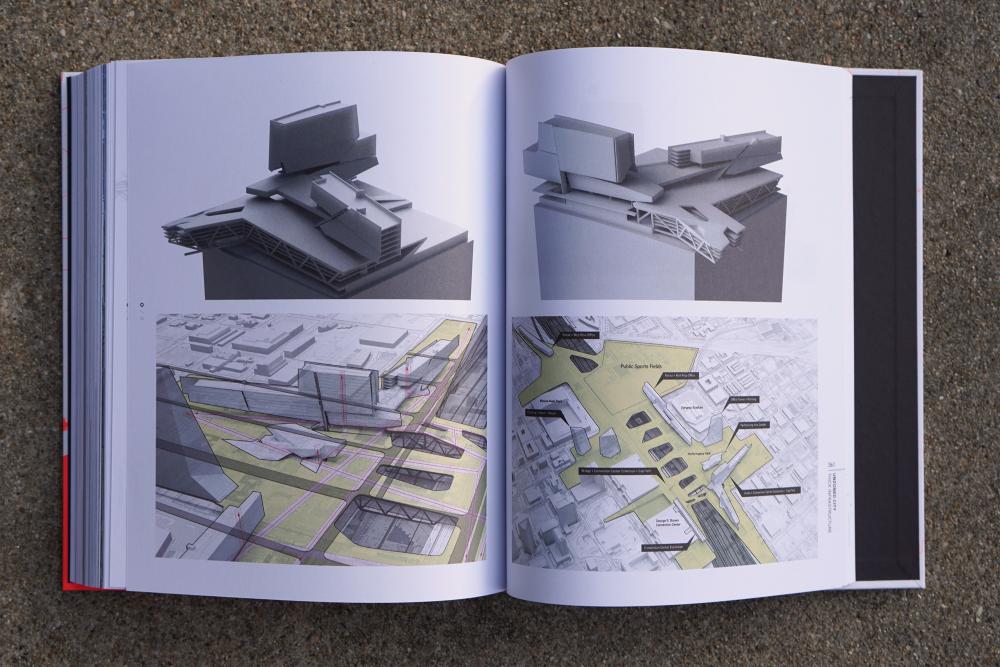

Developer City, led by Peter Jay Zweig, explores acupunctural strategies for transforming Houston’s downtown from a space of transience and homogeneity to one that embodies urban intensity and environmental compatibility. Through a mix of landscape, structure, and linkage, proposals suggest a phased approach to addressing flooding, reducing vacancy, creating destinations, and imbuing connectivity. Through their nodal approach, these phases ultimately aggregate to a “reimagined” downtown described as an “extensive park.” Forms clearly delineate proposed flows, either to carve space for stormwater detention or paste programmatic parasites on existing buildings. The overall effect is surprising: downtown Houston as an undulating landscape, more open, wilder, and relatively un-built, all counterintuitively achieved through structure. While the feasibility of realizing these visions is questionable, the invigoration of downtown with multifunctional programmatic scaffolds is compelling and pragmatic in principle.

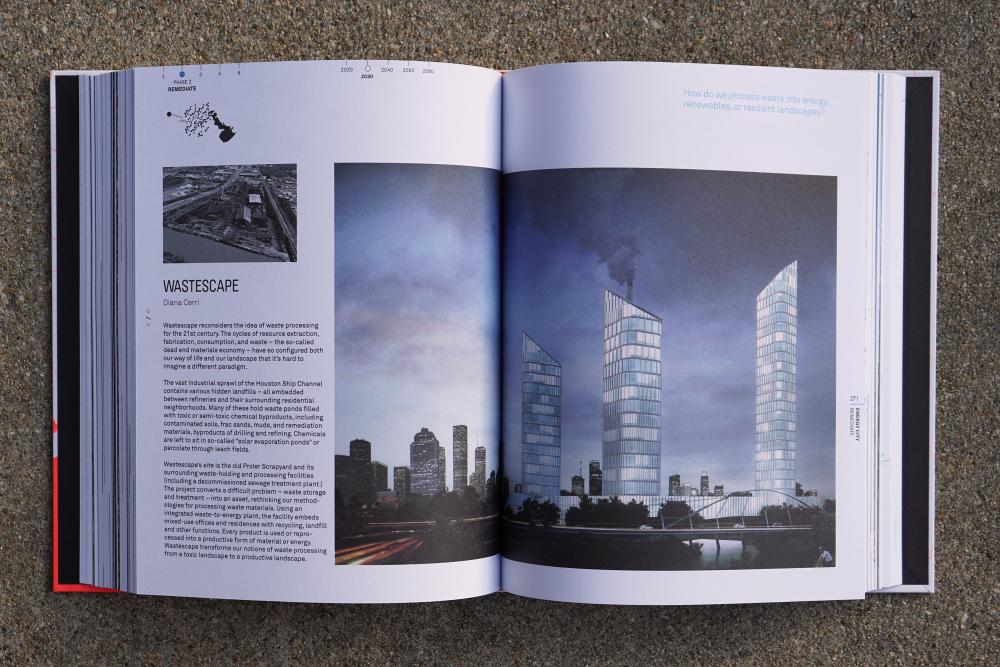

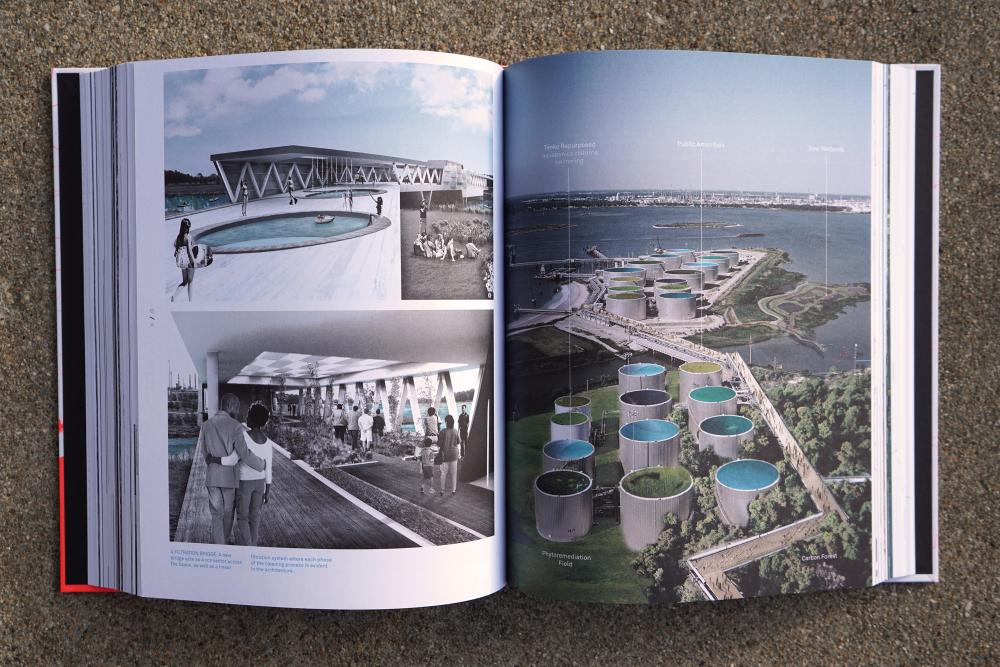

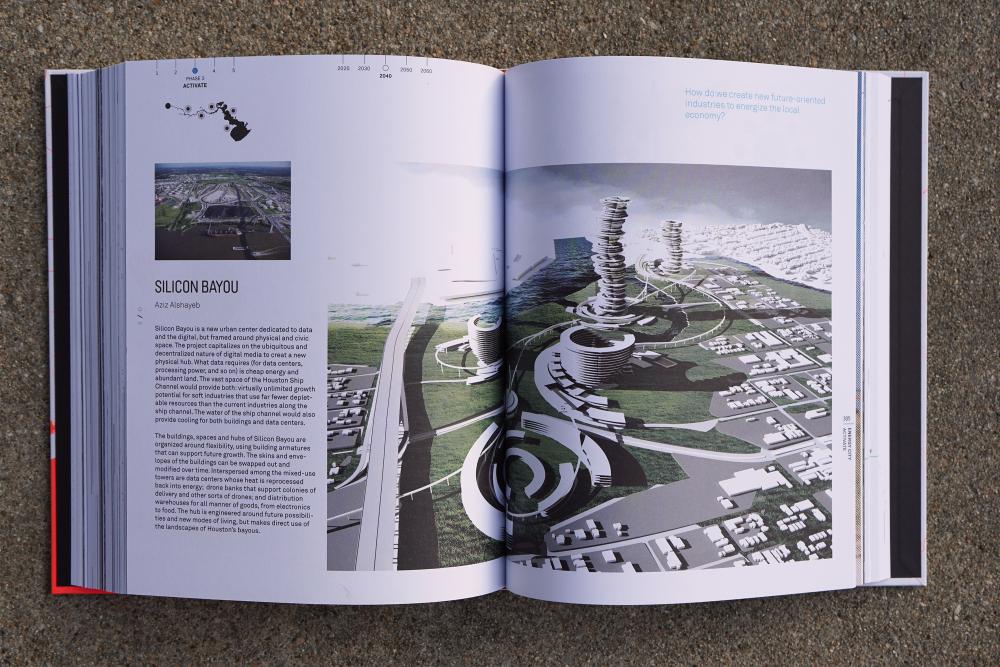

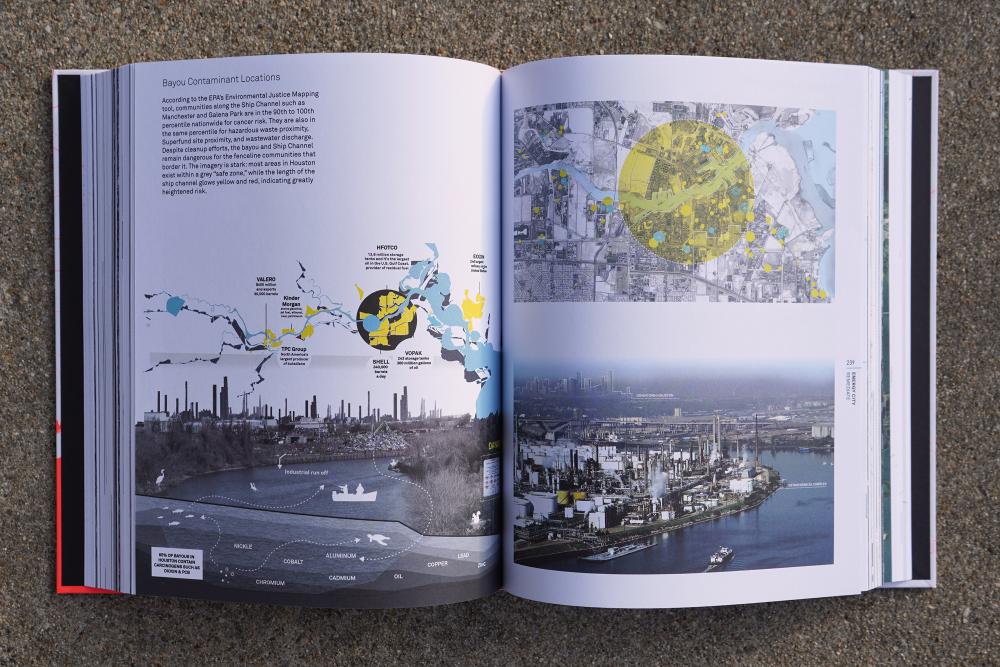

Energy City, led by Matthew Johnson, considers the landscape of Houston’s energy economy. This section “reimagines the ship channel’s industrial sprawl,” and proposes a landscape of “ecological opportunity and resilience.” The problems defining the petropolis—toxicity, pollution, sprawl, and flooding—are addressed through projects that prioritize both mitigation and transformation. Projects hybridize landscape and urban form—while providing interesting contributions to the challenging and impending question of post-peak oil urbanism in Houston.

The ideas and projects centered around remediation, infrastructural transformation, and economic processes are especially interesting. If architectural speculation aims to be relevant in contemporary discourse, then expanded considerations of economic influences and their associated infrastructures must be considered. Energy City’s proposals illustrate how viable postindustrial urbanisms might integrate alternative economic functions such as tourism, recreation, tech, education, and housing. The students challenge an expanding drosscape by suggesting novel architectures for challenging sites. Infrastructural evolutions such as a regional transit hub and an aggregated port facility stand out. Through its regional reorientation, this section achieves an ecological perspective that could have massive positive impacts.

Unzoned City, led by Jason Logan, examines the opportunities presented by Houston’s notorious lack of zoning. The geography in question is the result of a fascinating mapping exercise that identifies “residual territories”—spaces free from “the city’s loose network of municipal codes and deed restrictions.” Logan writes that regardless of the existence of unregulated islands, it’s rare that projects utilize these opportunities; instead, they frequently produce “relatively generic, mediocre, and unexceptional forms of urban development.”

Unzoned City explores the potential for meaningful utilization of these unregulated zones. The expanded uses of freeway corridors are a highlight. Through strategies of cap parks, open spaces, and programmatic mixing, these spaces are recast from dividers to aggregators. The projects embody the aspirational ethos that “city development, community resources/organizing, public/private space, and city infrastructures do not have to be mutually exclusive priorities.”

Interspersed with these student projects are thoughtful essays by Johnson and Logan (who practice together as LOJO), photographic sequences, and interviews that support the studio work. Architectural writing and interviews can be unintelligible at times, but thankfully the texts in Houston Genetic City are understandable. They concisely review the forces that shape the city and theorize what to do next.

The creative studio work is graphically exciting and well-researched, despite some spelling and editing errors along the way. Seen together, the spreads showcase much-needed solutions while awaiting a receptive systemic context—or a developer equal parts megalomaniacal and altruistic. The work also serves as a strong argument that transdisciplinary practice is the way forward, a call that echoes a Bruce Mau poster for Rice Architecture over twenty years ago: “The blurring of our boundaries suggests the shape of a new terrain.” Finally, it repeats the clear directive that ecological concerns ought to be central to every building, regardless of its program.

Houston Genetic City is the next chapter of big urban ideas about Houston that builds on the speculations of thinkers like Lars Lerup and others. The text challenges the status quo and presents ideas with transformative potential for broader consideration. At the core of the book is a dynamic ecological perspective and an orientation towards addressing “important problems.” These are positive principles that should be central to architectural discourse if the goal is to successfully generate “more than new shapes.”

Adam Scott is a landscape designer at SWA group in Houston.